ST. LOUIS βÄî Fimbrion Therapeutics, a small but successful biomedical research business based in the cityβÄôs Cortex Innovation Center, was close to developing a key drug in the arsenal against tuberculosis, the worldβÄôs deadliest infectious disease.

After working five years and receiving nearly $4 million in small business innovation funding though the National Institutes of Health, last fall celebrated a glowing review by the NIH that all but guaranteed the company would receive the last grant it needed to develop the final version of the drug.

The National Institutes of HealthβÄôs James Shannon building is seen on the agencyβÄôs campus in Bethesda, Maryland.

Another review in February moved things along, and staff expected money to begin flowing in March.

Instead, on May 14, came devastating and mysterious news: the grant was denied after failing a βÄ€foreign risk assessment.βÄù

People are also reading…

Fimbrion CEO Thomas Hannan says heβÄôs baffled because the company has no foreign ties. His effort to get an explanation was refused in an email: βÄ€NIH will not provide information regarding the specific details of identified risks, as this information involves security sensitivities.βÄù

The NIH decision threatens FimbrionβÄôs survival. The seven-member company has had to lay off two of its three chemists, and the rest of the employees are now working part-time while waiting to hear if three smaller grant applications for new projects will be funded or denied for the same reason.

βÄ€We just are dumbfounded,βÄù Hannan said. βÄ€Now we have these three grants that basically, if we donβÄôt get these, then weβÄôre probably going to have to shut down.βÄù

Since 2022, the NIH and other federal agencies have required private companies applying for grants through the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) to disclose all relationships with foreign countries in order to assess security risks.

That assessment effort, however, has recently come under fire by some federal Republican lawmakers who say it is failing to protect against funds and innovation ending up in the hands of foreign adversaries βÄî namely China.

ItβÄôs unknown if Fimbrion is caught up in an unusual or new crackdown. Requests sent to the NIH by the Post-Dispatch for information about the process went unanswered.

, a Washington University professor whose infectious disease research lab partners with Fimbrion, said other companies are facing the same challenges but are afraid to speak out.

βÄ€There are stories exactly like ours also here in Κϋάξ ”ΤΒ,βÄù Stallings said. βÄ€There are other people with their SBIRs that were supposed to be funded and also, for an unknown reason, are no longer getting funded after going through this foreign risk assessment review.βÄù

Because the actions are coming amid efforts by President Donald TrumpβÄôs administration to βÄî the largest public funder of biomedical research in the world βÄî scientists say they are skeptical the efforts have anything to do with safety.

βÄ€This is just so out of left field. This just doesnβÄôt make any sense,βÄù Hannan said. βÄ€So, is this an error or was this something malicious? Like, are they using this not to fund our grant?βÄù

Delays and uncertainty at the NIH are hampering medical advances and economic growth not just in academia but also among small businesses critical to quickly advancing discoveries, scientists warn.

Κϋάξ ”ΤΒ, the home of research powerhouse Washington University, is especially vulnerable. Its medical school among all medical schools for the amount it receives in NIH funding, and works closely with the entrepreneurs and startups drawn to the burgeoning Cortex district.

βÄ€ItβÄôs kneecapping science and medicine, and itβÄôs going to have a huge impact on the Κϋάξ ”ΤΒ area,βÄù Stallings said. βÄ€Washington University and the Barnes-Jewish (health care) system are huge employers here, and itβÄôs something Κϋάξ ”ΤΒ is known for. People come here from everywhere to be part of this amazing place to do science and medicine.βÄù

βĉReally dishearteningβÄô

University of Wisconsin researcher Kip Ludwig shared a similar experience to FimbrionβÄôs . Ludwig was partnering with San Francisco-based Presidio on an SBIR grant to study nerve stimulation to treat heart failure.

Three weeks after learning in February that their grant would be funded, the application was removed after a foreign risk assessment despite not having any known foreign connections.

βÄ€ItβÄôs a lot of time and effort to write an SBIR grant that scores within the payline for a very competitive review process, and really disheartening that you wonβÄôt even be told what the issue was,βÄù Ludwig wrote. βÄ€This is very concerning for transparency.βÄù

Like Fimbrion, the notice from NIH explained that assessment was done outside their purview: βÄ€NIH grants management and program staff do not receive specific information on foreign risk assessments and will not be able to provide further details.βÄù

In an email to the Post-Dispatch, Ludwig said heβÄôs had a handful of companies reach out to tell him after seeing his post revealing that they had the same thing happen to them.

βÄ€The companies being flagged that IβÄôm aware of have no direct connection to a foreign country of concern, and have no clue why they were flagged,βÄù he wrote.

In fiscal year 2024, about 4,000 recipients were awarded $4.7 billion through the SBIR and similar STTR grant programs, known as AmericaβÄôs Seed Fund.

The programs have existed since 1982 and have been βÄî supporting tens of thousands of jobs a year, producing more than 70,000 patents and leading to the creation of hundreds of public companies.

But Republican lawmakers have recently raised alarm bells over what they say is βÄ€systematic exploitationβÄù of the programs by China through avenues such as government-linked venture capital firms, research partnerships with American universities, and talent recruitment programs.

GOP lawmakers flag concerns

In February, Republican chairs of three U.S. House committees to the heads of 11 different federal agencies that issue SBIR and STTR awards, which includes the Department of Health and Human Services that oversees the NIH, as well as the departments of Defense and Energy.

βÄ€It has become increasingly clear that American taxpayer-funded innovation is being siphoned off to fuel the technological ambitions of our foremost adversary,βÄù the letter states, citing a 2021 report commissioned by the Pentagon that found cases of China using the programs to support defense and military efforts.

The letter seeks information about the federal agenciesβÄô foreign assessment efforts and ways the lawmakers can strengthen safeguards when the SBIR and STTR programs are set to expire Sept. 30 and must be reauthorized by Congress.

Since the 2021 report, federal agencies have been required to create programs to mitigate foreign involvement risks, but some lawmakers say it wasnβÄôt enough.

U.S. Sen. Joni Ernst, R-Iowa, as chair of the Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, that states large SBIR grants continue to be awarded by the Defense Department to six companies with alleged ties to China.

Ernst also , urging his agency to investigate the six companies.

Soon after the letters were sent, on May 1, it would not allow any NIH-funded researchers in academia or business to contract with foreign institutions until the agency figures out a new way to monitor the practice, no later than Sept. 30.

βÄ€By creating a more unified view of where NIH dollars are going, we are strengthening public trust and improving accountability of federal dollars,βÄù NIH Director Jay Bhattacharya wrote.

Jay Bhattacharya, director of the National Institutes of Health, speaks during an event in the Roosevelt Room at the White House, Monday, May 12, 2025, in Washington.

Scientists, however, say this hampers the innovation and speed of research, which relies on interdisciplinary and niche expertise around the world.

βÄ€This is work that will come to a screeching halt,βÄù said John Tavis, director of the , whose research into a cure for hepatitis B involves an organic chemist in Greece who has developed a way to create the particular molecules needed for the research.

Tavis said his grant application was just pulled by the NIH because it failed to include a βÄ€foreign justificationβÄù form. Tavis called it a minor oversight that in the past he would have been allowed to rectify as the application went through the review process.

Now, Tavis said, he is facing having to resubmit his application in a year or not being able to work with an essential collaborator.

βÄ€It appears as if they are taking a hard line, essentially looking for reasons to disallow grant applications that contain items that are questionable to the administrationβÄôs political viewpoint, such as collaborating with non-U.S. scientists,βÄù Tavis said.

Ludwig, the Wisconsin researcher, says the foreign assessment process has gone rogue.

βÄ€Wildly inexperienced/completely unqualified people have been put in charge of this process under the Trump administration, who were arrogant enough to make drastic changes in implementation quickly without ever bothering to talk to anyone with actual relevant background/domain specific knowledge,βÄù he wrote in an email.

FimbrionβÄôs track record

Fimbrion was founded in 2012 with a mission to develop anti-bacterial drugs that help prevent infectious diseasesβÄô increasing resistance to antibiotics.

It was very successful, thanks to SBIR funding, in developing a small-molecule drug to treat urinary tract infections using a technology discovered by Washington University.

FimbrionβÄôs success in creating the drug led to a , which recently finished the first phase of testing the treatment in humans.

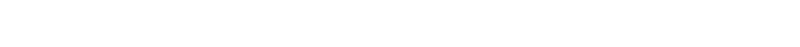

βÄ€We were kind of like the NIH poster child,βÄù said Laurel McGrane, FimbrionβÄôs director of chemistry. βÄ€What the NIH can do for you is really take a small business that has no investor money whatsoever, and if you apply for grants, we can help you get the whole way.βÄù

Fimbrion was on a similar trajectory with its tuberculosis treatment, a process also developed by WashU.

βÄ€We donβÄôt have the capacities or capabilities to actually develop a new drug to be put into humans so we needed to find a business partner who would be interested in working with us,βÄù said Stallings, the WashU professor.

Fimbrion has over the past five years received about $3.6 million in SBIR funding to develop the tuberculosis drug, and was hoping for another $3 million over the next three years.

βÄ€The NIH has already made a significant investment in this project, so ending it when it has been very successful is wasting that prior investment,βÄù Stallings said. βÄ€Not to mention that this project could have resulted in saving countless lives.βÄù

This 2006 electron microscope image provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria, which causes the disease tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis is one of the most difficult bacterial infections to treat because of its evolving resistance to antibiotics. Current treatment involves taking a four-drug cocktail up to six months, which can come with serious side effects.

The drug Fimbrion is developing treats both active and latent tuberculosis by targeting how the bacteria breathes βÄî a new target that has not developed antibiotic resistance.

McGrane said the company had exceeded its research milestones, creating a potent and stable-enough drug to treat the infection in mouse models. Scientists needed another round of funding to test one last change they believed would prove it to be a powerful candidate to be tested in humans.

βÄ€These are the assays you need to run if you want people to take an interest in your molecule,βÄù and fund large clinical studies, McGrane said.

McGrane said she expects to hear more stories about small businesses having to shut their doors as their grants are denied with no transparency as to why, which is not what researchers are used to from the NIH.

Hannan agreed.

βÄ€At a certain point, itβÄôs just not worth it, right?βÄù he said. βÄ€If the whole point of this is for innovation, a small company is going to be like, βĉYou know, this is too much drama, too much uncertainty.βÄô Because thatβÄôs the way I feel. IβÄôd rather do something else at this point.βÄù

Red states and blue states alike are poised to lose jobs in research labs and the local businesses serving them. Ripple effects of the Trump administrationβÄôs crackdown on U.S. biomedical research promise to reach every corner of America. It's not just about scientists losing their jobs or in the local economy their work indirectly supports, but also about patient health.